What Rock City's Billboards Can Teach Chattanooga Businesses About Digital Marketing

Nate Sanden

Founder & CTO

November 3, 2025

Published

You remember them, don't you?

You were seven years old in the backseat of your parents' station wagon, somewhere between Chattanooga and the Florida panhandle. The road was a two-lane ribbon cutting through farmland. Your sister was asleep against the window. And then you saw it.

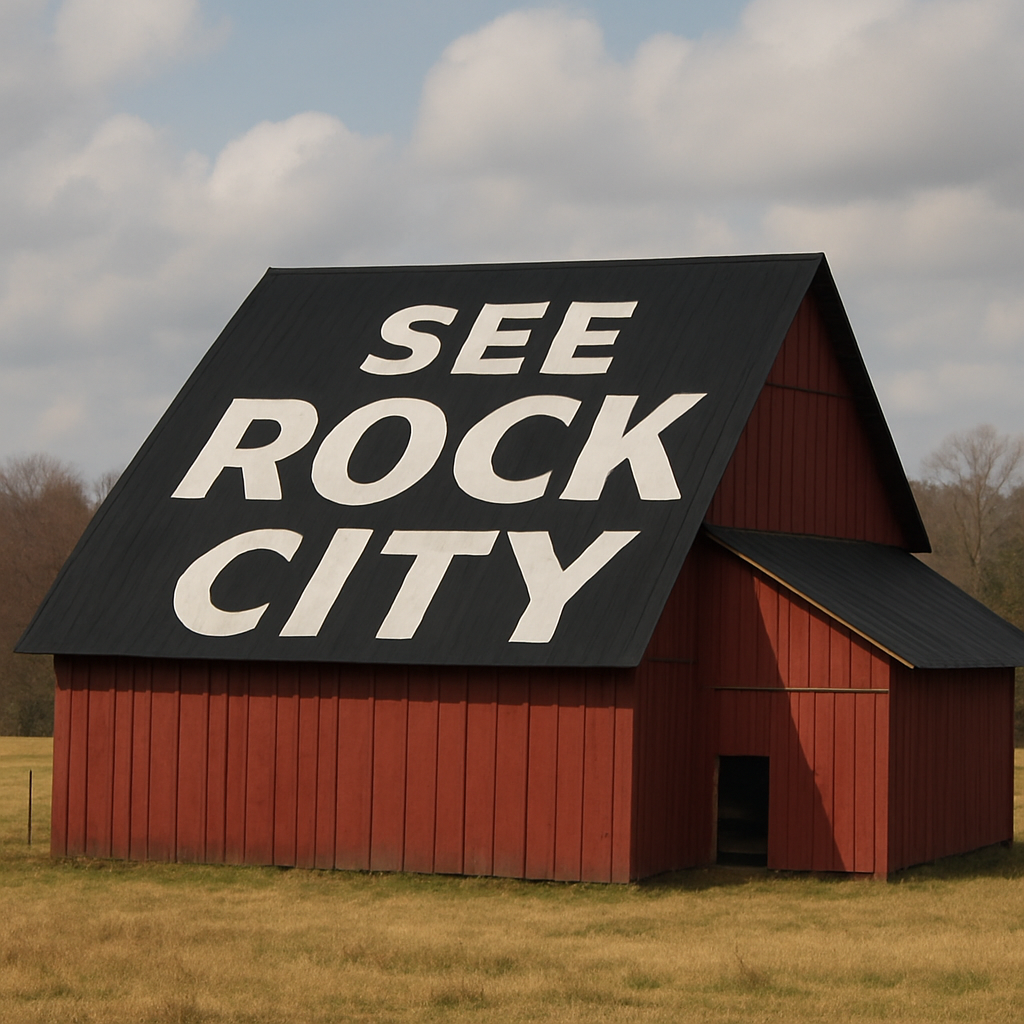

SEE ROCK CITY

Three words. White letters on black paint. Stretched across the side of a barn you'd never see again.

You asked your dad what Rock City was. He didn't know. You asked your mom. She shrugged. But for the next 200 miles, you kept seeing those barns. Different sizes, different farms, same message. By the time you reached the Georgia line, you were begging to go.

That was the plan all along.

The "See Rock City" barn campaign is one of the most successful marketing efforts in American history. It ran for over three decades. At its peak in the 1950s, 900 barns across 19 states carried the message. And it all started because a business on top of Lookout Mountain was failing, desperate, and willing to try anything.

This isn't a nostalgia piece. This is about what a hand-painted barn from 1935 can teach your Chattanooga business about marketing in 2025. Because the principles that turned Rock City from an obscure mountain garden into a cultural icon are the same principles that will make your business impossible to ignore online.

The Desperation That Breeds Innovation

Frieda Utermoehlen Carter had a whimsical imagination and a deep love of German folklore. In 1932, she opened Rock City Gardens on 700 acres atop Lookout Mountain. She laid out the "Enchanted Trail" herself, reportedly using a ball of red string. She transplanted over 400 species of native wildflowers. She imported German statues of gnomes and fairytale figures and created a place called Fairyland.

It was beautiful. It was remote. And nobody came.

Her husband, Garnet Carter, was a natural-born salesman. He'd already made a fortune inventing Tom Thumb miniature golf, a franchise that swept the nation. But his wife's garden presented a problem he'd never faced before. You can put a miniature golf course anywhere. You can build it next to a gas station, a shopping center, a busy intersection. People will stumble onto it.

But a garden on a mountaintop? People don't just happen to be passing by.

For the first few years, Rock City languished in obscurity. This was the Great Depression. People didn't have extra money for whimsical mountaintop gardens. Garnet Carter watched his investment bleed out, season after season. And then he had what history would call a "brainstorm."

But it wasn't really a brainstorm. It was theft.

The Bloch Brothers Tobacco Company had been painting "Mail Pouch" advertisements on barn sides since the turn of the century. Carter saw it working for tobacco. He decided to make it work for tourism. This is the first lesson: your best marketing idea probably already exists. You just need to be desperate enough, or smart enough, to adapt it.

So in 1935 - or maybe 1936, or maybe 1937, the records are fuzzy and that fuzziness became part of the legend - Garnet Carter hired a self-taught painter from Chattanooga to start painting barns.

The painter's name was Clark Byers. And for the next 34 years, he would become a folk hero.

The Man Who Painted 900 Barns

Clark Byers was born in 1915. He wasn't formally trained. He didn't go to art school. He was just a guy who could paint a straight line and wasn't afraid of heights.

Between 1935 and 1969, Byers painted approximately 900 barns across 19 states. He traveled the back roads of the South and Midwest with buckets of lampblack and linseed oil. He climbed onto roofs that hadn't been climbed in decades. He braved bulls in pastures, slippery shingles in rainstorms, and lightning bolts that split the sky while he worked.

The stories about Byers are repeated so often they've taken on the quality of myth. The farmer who warned him about the bull. The barn roof so steep he had to tie himself to the chimney. The time he kept painting through a thunderstorm because the farmer was waiting, and Byers had given his word.

And then there's the story that ended it all.

In 1968, somewhere near Murfreesboro, Tennessee, Clark Byers was painting a barn. He inadvertently made contact with a high-voltage wire. The shock nearly killed him. He was partially paralyzed. It put him out of action for months. When he recovered enough to work again, he decided he'd had enough. In 1969, at 54 years old, Clark Byers retired.

Why does this matter?

Because marketing isn't about logos and slogans and clever taglines. It's about the stories people tell. And the story people told about Rock City wasn't just "we saw a sign." It was "there's a man who risked his life to paint 900 barns, and he almost died doing it."

That's the second lesson: people don't buy products. They buy stories. And the best stories aren't about your business. They're about the people behind it.

Clark Byers gave Rock City a soul. Your business needs one too.

The Depression-Era Barter That Changed Everything

Let's talk about the deal.

Garnet Carter needed barns. Farmers had barns. But this was 1935. The Depression had gutted rural America. Farmers didn't have money to spare, and Carter didn't have money to spend. So he made them an offer that didn't require cash.

Here's what the "usual arrangement" looked like:

- A free, professional paint job for the entire barn

- An armload of promotional goods (the now-famous Rock City thermometers, sometimes bathmats)

- Free passes to Rock City for the farmer and his family

- For farmers who didn't want trinkets, a modest cash payment of $3 to $10

That was it. For about $40 to $50 in total cost, Carter got a massive, hand-painted billboard that would last for decades.

The genius wasn't the low cost. The genius was understanding what the farmer valued.

During the Depression, a farmer's barn was an asset, but maintaining it was a liability. Paint was expensive. Labor was expensive. A peeling, decaying barn was a visible symbol of financial struggle. Carter's offer turned a farmer's liability into a maintained asset. The farmer got a barn that looked proud and cared-for. Carter got a billboard.

This is the value exchange. And it's the third lesson: you don't need a big budget. You need to understand what the other person actually wants, and give them that in exchange for what you need.

Now, here's where it gets strategic.

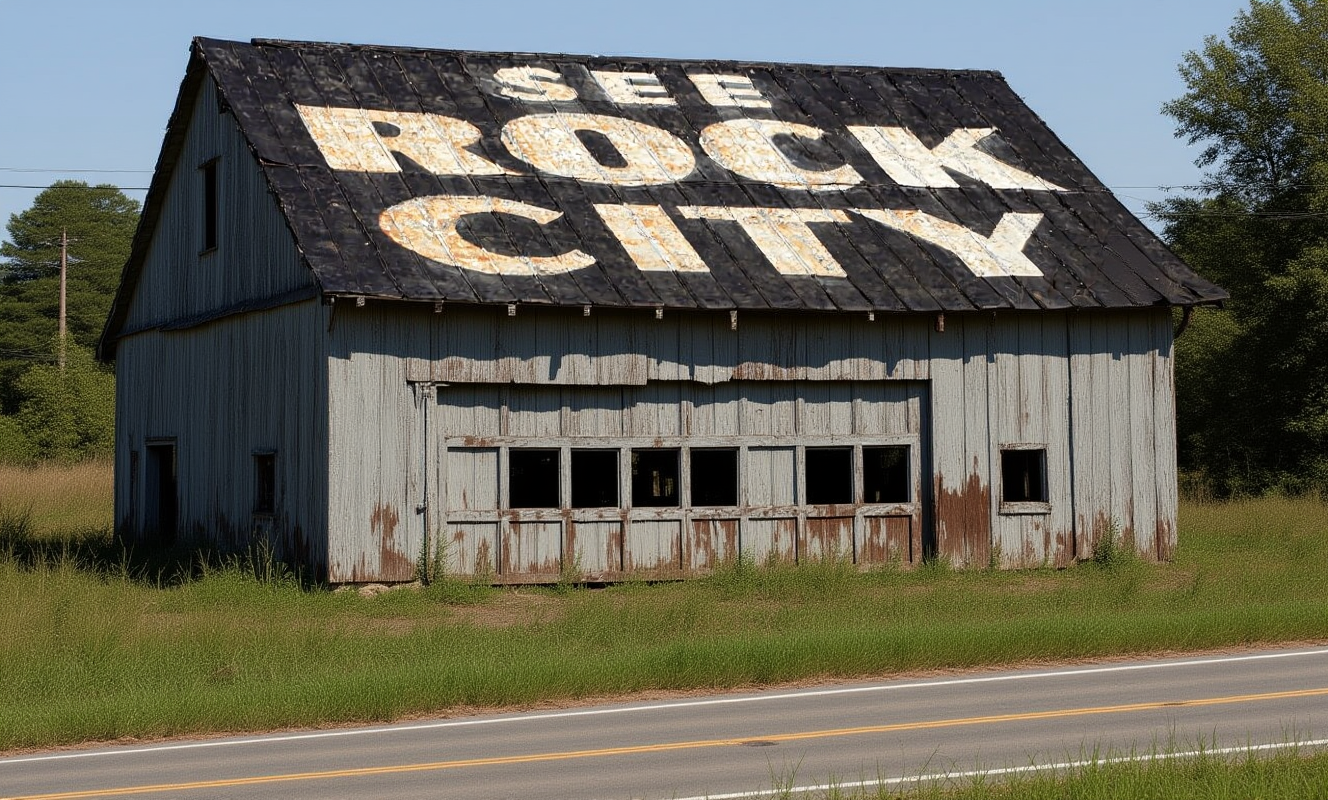

Byers didn't just paint any barn he could find. He was a media planner before media planning was a profession. He demonstrated a remarkable skill at selecting the best canvas for signs. Barns were chosen for maximum visibility. He looked for barns facing the highways that led toward Chattanooga. He looked for barns at the bottom of hills, at curves in the road, at places where southbound motorists would have no choice but to see them.

One barn on Tennessee State Route 68 was painted at the bottom of a hill at a curve in the highway. It was, quite literally, impossible to miss. That wasn't luck. That was strategy.

The network spanned 19 states, from the Florida line to the Canadian border, from the Carolinas to Texas. It targeted snowbirds and Sunday drivers traveling the major arteries of the South and Midwest. The first barn was placed along the Dixie Highway, the main tourist route from Chicago to Florida.

This was a sophisticated advertising network built with nothing but paint, persuasion, and a farmer's desire for a maintained barn.

The Accidental Psychology of "See Rock City"

Let's look at the slogan itself.

SEE ROCK CITY

Three words. No explanation. No picture of the view. No gnomes, no fairyland, no "7 states from one mountaintop." Just a command.

This is where the campaign transcends clever into genius. And the genius, like most genius, was probably accidental.

"See Rock City" is a perfect example of what modern psychologists call the "curiosity gap." The principle is simple: when people sense a gap between what they know and what they want to know, they are compelled to bridge it. The slogan creates a cognitive itch.

Think about it from the backseat of that station wagon. You see the first barn. You don't know what Rock City is. You're curious, but not enough to make a fuss. Then you see another barn. Then another. By the tenth barn, you're obsessed. The slogan has teased you for 150 miles, but it has never told you anything. The only way to resolve the ambiguity, the only way to scratch that itch, is to obey the command.

See Rock City.

The ultimate proof of this principle's success? The phrase became ubiquitous, familiar even to people who had no idea what it meant. The curiosity became more famous than the attraction itself.

But Byers didn't just paint the same three words on every barn. Because he painted everything freehand, he adapted the message to the medium. Small barns got the simple "See Rock City." Large barns got the expanded pitch: "See 7 States from ROCK CITY atop Lookout Mt. near Chattanooga, Tenn." Some barns claimed it was the "World's 8th Wonder." Others promised "When You See Rock City, You See the Best."

And as travelers got closer to Chattanooga, the barns started counting down. "35 Miles to Rock City."

This is the fourth lesson: mystery outperforms explanation. And repetition, when done with variation, builds anticipation.

The barns weren't just signs. They were narrative breadcrumbs. A traveler from Michigan would see the first "See Rock City" sign in Ohio, the "See 7 States" pitch in Kentucky, and the "35 Miles" countdown in Tennessee. The journey became part of the experience. By the time they reached Lookout Mountain, they weren't just visiting a garden. They were completing a story that had started 500 miles ago.

You can't buy that kind of engagement. You can only engineer it.

900 Barns to 40: The Decline

The glory days ended abruptly.

In 1965, First Lady Bird Johnson championed the Highway Beautification Act. The goal was noble: clean up America's roadsides, remove the eyesores, restore natural beauty. The act prohibited advertising within 600 feet of a federal highway. Byers was required to paint over any signs that violated the new law, destroying a large portion of Rock City's advertisements in a single stroke.

Then came the interstates. By the late 1960s, the nearly complete interstate system had lured travelers away from the old two-lane highways where the barns lived. The new roads bypassed the curves and hills and small towns entirely. The barns were still there, still boldly painted, but nobody was seeing them.

And then, in 1968, Clark Byers touched that high-voltage wire. He retired the next year. The man who had built the empire was gone. The roads had moved. The law had changed.

The campaign, for all practical purposes, was over.

In 1974, an amendment to the Highway Beautification Act provided a reprieve. "Landmark signs" that had been lawfully painted before 1965, signs with historic or artistic significance, could be grandfathered in. They didn't have to be destroyed. The surviving barns were saved.

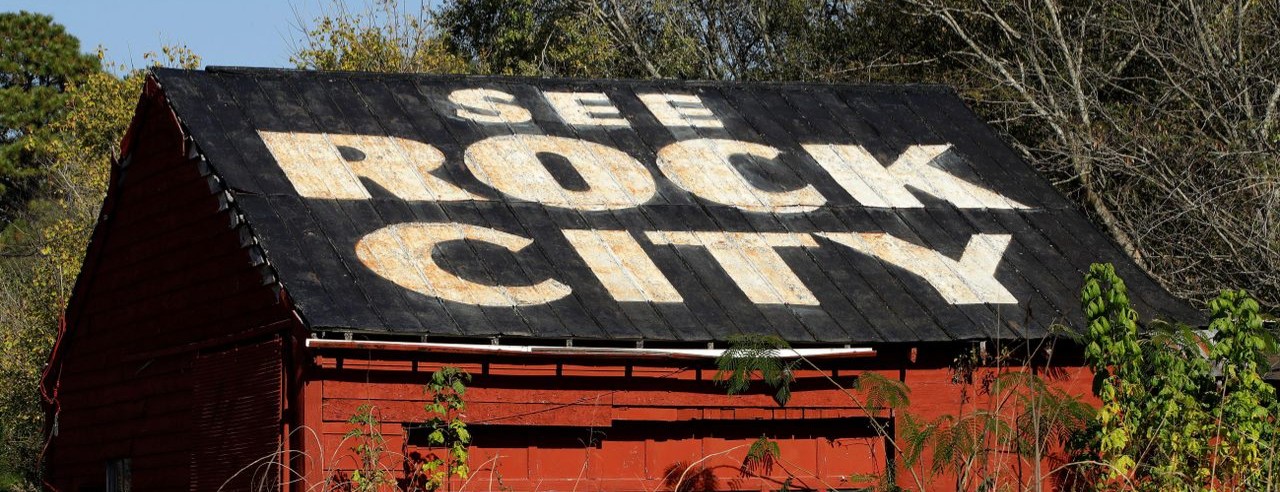

But they weren't maintained. Not the way Byers had maintained them. And one by one, they began to fall.

At the campaign's peak, 900 barns carried the message. By 1994, only about 250 remained. By 1998, that number had dropped to 200. By 2014, 100. By 2021, around 50. Today, in 2025, there are approximately 40 to 42 barns still standing.

And here's the cruel irony: when an 80-year-old barn finally succumbs to time and weather, when it collapses or burns or gets torn down by a developer, it cannot be replaced. Modern regulations won't allow it. The collection of barns is a finite, non-renewable resource.

But that's not the end of the story. Because something remarkable happened in the decades after the campaign "died."

The barns became more valuable than ever.

From Advertisement to Corporate DNA

Somewhere along the way, the barns stopped being advertisements and became something else. They became genuine highway Americana. They became symbols of a bygone era, of long-ago family vacation trips on twisting two-lane highways before the interstates homogenized American travel.

For millions of people, the sight of a Rock City barn triggers instant nostalgia. Not for the attraction itself, necessarily, but for the feeling of being seven years old in the backseat, watching the world scroll by through the window.

Museums began preserving them. The American Sign Museum in Cincinnati, Ohio now features Rock City signs as cultural artifacts. Rock City itself pivoted from expansion to restoration. Byers' successors still paint barns today, but they're not adding new ones. They're treating the surviving barns like historic landmarks.

In 2021, Rock City partnered with the Tennessee Titans to restore three barns in East Tennessee, featuring co-branding with the NFL team. Visual artist "doughjoe" painted them as part of a "Tennessee Tough collaboration." This wasn't about customer acquisition. It was about public relations, shared heritage, and associating the Rock City brand with Tennessee pride.

The barns had transformed from a marketing tool into an appreciating asset. What was once an advertisement is now priceless.

And then came 2025.

In June of this year, the parent company, "See Rock City, Inc." (yes, the company itself was named after the slogan), announced a strategic rebrand. The company had diversified over the decades. It now owned multiple hospitality brands, including Clumpies Ice Cream Co. The old name no longer fit. So they rebranded to "Rock City Enterprises."

And the logo they chose to represent the entire corporate portfolio? The birdhouse.

You might not know this story. Clark Byers originally tried to create miniature barn mailboxes for the farmers. The U.S. Postal Service denied him. So he added holes to his miniature barn design and turned it into a birdhouse instead. Those birdhouses became as iconic as the barns themselves.

Ninety years after the first barn was painted, the symbol born from that Depression-era marketing campaign isn't just a cherished part of the brand. It is the brand. The barn-turned-birdhouse is now the core corporate identity of a multi-million dollar enterprise.

This is the fifth lesson, and it's the most important one: the best marketing doesn't just drive sales. It outlives its own obsolescence to become the DNA of the business itself.

What This Means for Your Chattanooga Business

So what does a 90-year-old barn campaign have to do with your HVAC company, your law firm, your restaurant, or your marketing agency in Chattanooga in 2025?

Everything.

Because the principles that turned Rock City from a failing mountaintop garden into a cultural institution are the same principles that will make your business impossible to ignore in a crowded digital landscape.

Lesson 1: Your best idea already exists. Adapt it.

Garnet Carter didn't invent roadside advertising. He stole it from a tobacco company and made it work for tourism. You don't need to reinvent digital marketing. You need to look at what's working in other industries, other cities, other contexts, and adapt it to your Chattanooga business.

What's your "Mail Pouch barn"? What's the idea that's been proven somewhere else, that nobody in your industry has tried yet?

Lesson 2: People buy stories, not products.

Nobody remembers Rock City because of the gnomes or the seven-state view. They remember it because of Clark Byers. The man who painted 900 barns. The man who was nearly electrocuted and kept going.

What's your story? Not your "About Us" page story. Your real story. The reason you started. The thing that almost killed the business. The person who bet on you when nobody else would. That story is your marketing. Tell it everywhere.

Lesson 3: You don't need a big budget. You need a value exchange.

Rock City scaled to 900 barns for $40 to $50 each because Garnet Carter understood what farmers actually wanted. Not money. Maintenance. Pride. A barn that didn't look like poverty.

What do your potential customers or partners actually want? Not what you think they want. What they actually value. If you can give them that in exchange for visibility, attention, or access, you don't need a massive ad budget. You need to understand human motivation.

Lesson 4: Mystery outperforms explanation.

"See Rock City" worked because it didn't explain. It didn't show pictures. It didn't list features and benefits. It just gave a command and let curiosity do the rest.

Your website, your social media, your ads - are they explaining too much? Are they giving everything away in the first three seconds? Or are they creating a gap that your prospect needs to close?

Stop telling people everything. Make them want to know more.

Lesson 5: Build something that outlives its purpose.

The barn campaign stopped being effective as advertising in 1969. But 56 years later, it's more valuable than ever. Because it transcended advertising and became culture.

What are you building right now that could become part of Chattanooga's fabric? What could you create that people will want to preserve, not because it's useful, but because it means something?

That's not a question with an easy answer. But it's the question that separates businesses that run ads from businesses that become legends.

There are 40 barns left. Maybe fewer by the time you read this. When the last one falls, it can't be replaced.

But the campaign itself? It's immortal. It's in museums. It's on corporate logos. It's in the memories of millions of people who saw those three words from the backseat and couldn't stop thinking about them.

Ninety years ago, a desperate man with a failing business and a bucket of paint created something that would outlive him, outlive the medium, and outlive the era.

Your Chattanooga business has that same opportunity. Not to paint barns. But to build something so fundamentally human, so strategically sound, and so culturally resonant that it transcends marketing and becomes legacy.

The question is: are you desperate enough to try?

Ready to Get Your Business Found Online?

Let's set up your complete online presence—website, Google, and Facebook—working together to get you customers